South Korea’s fringe views on a post-American Asia

Fantasies on the political fringe shape what people are willing to accept when reality shifts.

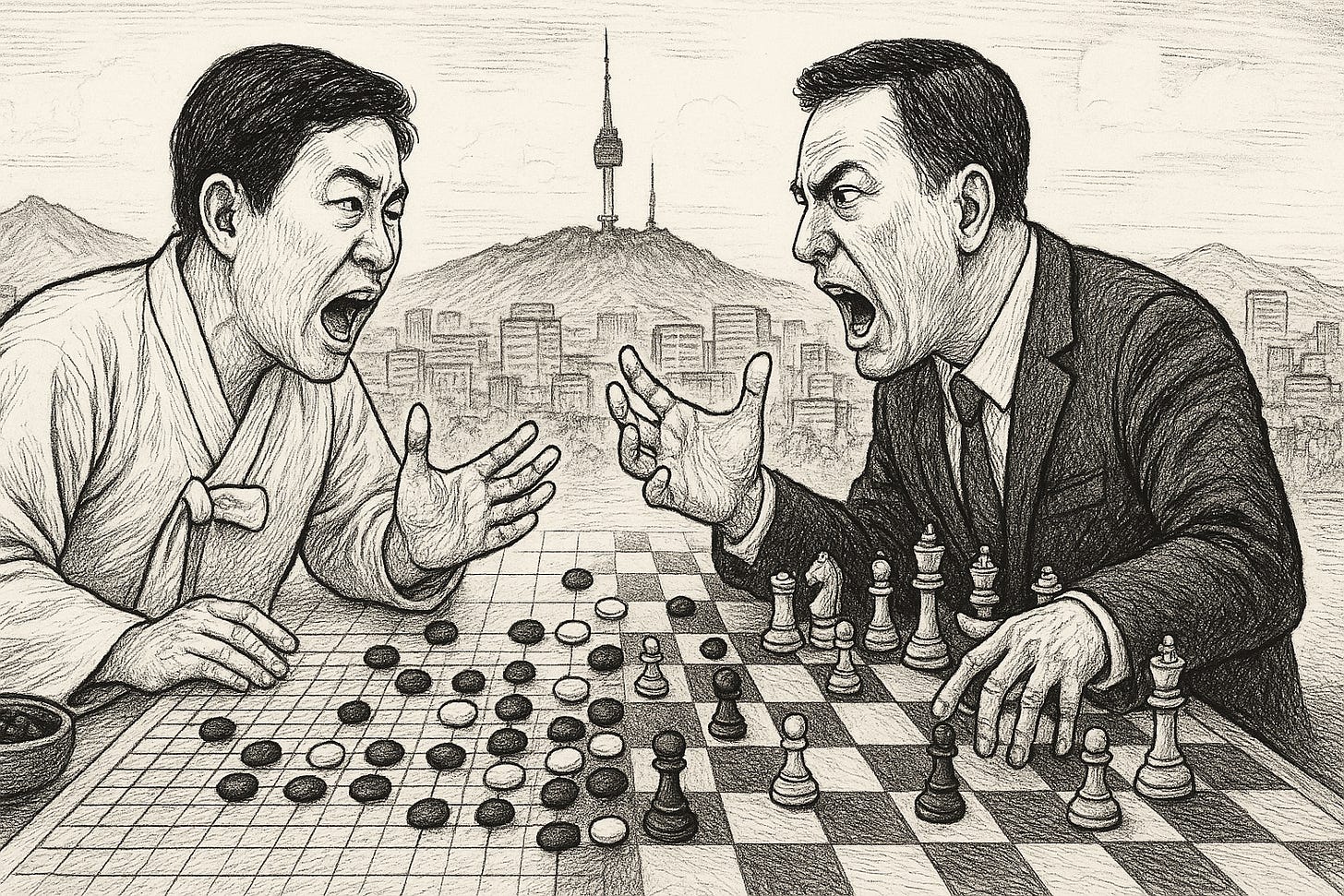

In South Korea, the idea of a post-American Asia—that is, a regional order no longer anchored by the U.S. alliance system—invites wildly divergent visions. Nowhere are these differences more vivid than at the ideological extremes.

On the far left and far right of South Korea’s political spectrum, the same scenario—the U.S. pulling back or leaving Asia altogether—is interpreted not just differently, but in diametrically opposed terms. One side sees opportunity; the other sees existential danger.

The extreme left imagines the end of American primacy in Asia as a long-awaited opening. Their logic is rooted in historical resentment and nationalist longing: the American presence, they argue, has artificially frozen the division of the peninsula. They see the 1953 armistice not as a peace mechanism, but as a leash.

If that leash were cut, if America’s deterrent were removed, the peninsula could “naturally” move toward unification—albeit on very different terms than the South Korean mainstream would accept. In their vision, a China-centered regional order would be more conducive to Korean reconciliation, even if that meant Seoul adapting to a new regional hierarchy with Beijing at the top.

There is nothing quiet or apologetic about this view. For the extreme left, Washington has not just blocked peace; it has actively sustained division. The continued presence of U.S. forces in Korea is seen as a provocation to North Korea, a justification for militarization, and a barrier to diplomatic innovation.

Once America leaves, they argue, the South will be forced to deal with the North on equal terms. “Neutralization” becomes the goal—pulling Korea out of its Cold War entanglements and anchoring it in a new Asian concert system led by China, with a unified Korea perhaps playing a Finland-style balancing role. For these voices, China is not the enemy; it is the region’s civilizational core, and Korea must return to it after a long Western detour.

Of course, this view sits far outside the mainstream. Most South Koreans, even on the progressive side, remain wary of Chinese intentions and skeptical of North Korea’s willingness to engage in good-faith unification. But on the far left, unification is an ideological goal that overrides strategic risk. A post-American Asia is welcomed because it breaks the deadlock imposed by a U.S. order that values deterrence over diplomacy and stability over transformation.

The extreme right, by contrast, sees the same scenario as the beginning of a geopolitical nightmare. In their imagination, the American exit is not an opening, but an abandonment. The loss of the U.S. alliance would expose Korea to what they view as the historical constants of East Asia: domination by stronger neighbors and vulnerability to external pressure.

Without U.S. backing, the region reverts to an older pattern of hierarchical power, where Korea must find a patron or be subsumed.

Here, the extreme right’s answer is simple: Japan. Recasting Japan as a partner rather than a historical enemy, they imagine a new anti-China bloc, a maritime alignment of liberal states that share the burdens of regional security. The loss of the U.S. anchor does not end the alliance mentality—it just transfers it. A stronger Seoul-Tokyo axis, perhaps bolstered by expanded cooperation with Taiwan or ASEAN states, becomes the substitute framework.

At the extreme, some even imagine the constitution of a “mini-NATO” for the Indo-Pacific, though such proposals ignore both Japan’s constitutional constraints and deep-seated Korean public resistance.

This view rests on fear. Fear of Chinese coercion. Fear of North Korean adventurism. Fear of abandonment. While the mainstream right may also share these concerns, the extreme right elevates them into a worldview that justifies closer alignment with any actor—even former colonizers—so long as it promises security and leverage. In their vision, Japan is no longer a source of trauma, but a necessary partner in an age where ideology is secondary to survival.

A post-American Asia demands new alliances, and history must be set aside.

The political center, of course, is far less dramatic. South Korea’s mainstream parties—whether conservative or progressive—do not seek a U.S. exit and continue to prioritize the alliance. But the extremes matter. Not because they dictate policy, but because they reveal the latent anxieties and aspirations buried in public discourse. What the far left and far right offer are not policies but imaginaries. They reflect unresolved questions about Korea’s identity, its place in Asia, and what it really means to be independent.

Crucially, both extremes increasingly agree on one thing: the U.S. presence in Asia is not permanent. Whether welcomed or feared, both sides now believe that the American era is ending. This is not a fringe idea anymore; it is creeping into the strategic calculations of think tanks, editorial pages, and even official documents.

What differs is the imagined aftermath. Will Korea tilt toward Beijing and pursue unification on China’s terms? Or will it double down on maritime partnerships and risk escalation with the North?

Perhaps what’s most striking is that both views rely on an almost cinematic reordering of Asia. The extreme left dreams of peaceful unification and Asian fraternity; the extreme right sees a clash of civilizations.

Both are fantasies, in the strict sense of being disconnected from political and strategic realities. Unification will not materialize simply because the U.S. leaves. Nor will Japan become Korea’s reliable protector overnight. The actual post-American Asia—if and when it comes—will be far messier, shaped by inertia, improvisation, and the persistence of risk.

But fantasies matter. They shape what people are willing to accept when reality shifts. And as U.S. commitment in Asia becomes less assured—with Trump’s transactionalism, domestic gridlock, and strategic overstretch—those fantasies may suddenly be called upon to fill the vacuum.

At that moment, when fantasies are suddenly be called upon to fill the vacuum, the extremes suddenly become highly relevant. They could be thought of as blueprints. And that is the danger.