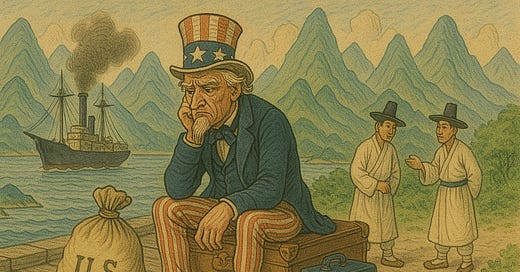

South Korea’s options in post-America Asia

The United States may not leave tomorrow, or next year, but when it does, the cost of not having prepared will be borne entirely by Seoul.

Hugh White’s recent essay in The Quarterly argues that Australia should be preparing now for the departure of the U.S. He notes “it is futile for Australia to frame its defence around U.S. deterrence of China when America itself is not serious about it.” His essay is understandably focused on Australia, but much of what he says applies equally to South Korea. Should South Korea be preparing now for the departure of the U.S.?

White argues that the United States will retreat from Asia not because it lacks military strength, but because political will is weakening as it becomes clear that it no longer makes strategic sense to sustain regional dominance. In past eras—during the First World War, the Second World War, and the Cold War—it made sense for the U.S. to project power across the globe to prevent any single state from dominating Eurasia. These conditions no longer apply.

Today’s world is multipolar, with power in Eurasia distributed among Europe, Russia, China, and India. Nuclear war is the only real threat to the U.S. and it will not risk this for Taiwan, South Korea, the Philippines or Australia. Simply, the U.S. no longer needs to impose order, and will instead act as an offshore balancer—intervening when necessary to prevent hegemony, but otherwise letting the regional powers constrain one another.

Applied to Korea, the essay suggests Seoul is at a strategic turning point. The longstanding reliance on the U.S. as a security guarantor is becoming increasingly uncertain as America reassesses its global role and retreats from regions where it no longer sees hegemonic necessity.

While the U.S. may remain present in a limited capacity, its commitment to extended deterrence will weaken, forcing Seoul to reconsider the viability of its dependency. This will be especially pressing as China consolidates regional influence and as U.S. domestic politics make sustained foreign commitments more erratic. South Korea, positioned at the fault line of great power rivalry, can no longer assume the credibility of U.S. protection is guaranteed.

White goes further to argue that the Korean Peninsula may ultimately be the precipitant that pushes America’s departure. North Korea’s development of intercontinental nuclear capabilities is a direct threat to the U.S. South Korea is increasingly less confident of U.S. extended deterrence. This erosion of trust has led to increasingly serious discussions in Seoul about pursuing an independent nuclear weapons program (see below).

If South Korea does take steps toward nuclearization, it could profoundly shake the foundations of the U.S.–Korea alliance. The fallout would not only weaken ties with Seoul but also raise questions about America’s broader position in Asia, including its alliances with Japan. As White notes, the Korean Peninsula may be “the final nudge that brings the American era in Asia to a close.”

Where does this leave South Korea today? Should South Korea be preparing now for the departure of the U.S.?