Storytelling in international relations

Thinktanks connect to the public because they tell stories. Scholars behind academic paywalls don’t.

International relations (IR) prides itself on complexity. Theorists build elaborate models. Graduate students master obscure jargon. Journals publish 30-page articles that few outside the discipline will ever read. It’s all very serious. But if the goal is to actually change policy — if the hope is to influence the people who make decisions about war, peace, and everything in between — then the whole enterprise starts to look like exhaustive and pointless wankery.

Because policymakers, as it turns out, don’t want your multi-level models or epistemological debates. They want something simple. They want a story. One that tells them who’s good, who’s bad, what went wrong, and how to fix it. And they’re not wrong. Stories stick. Data doesn’t. Narrative wins. Every time.

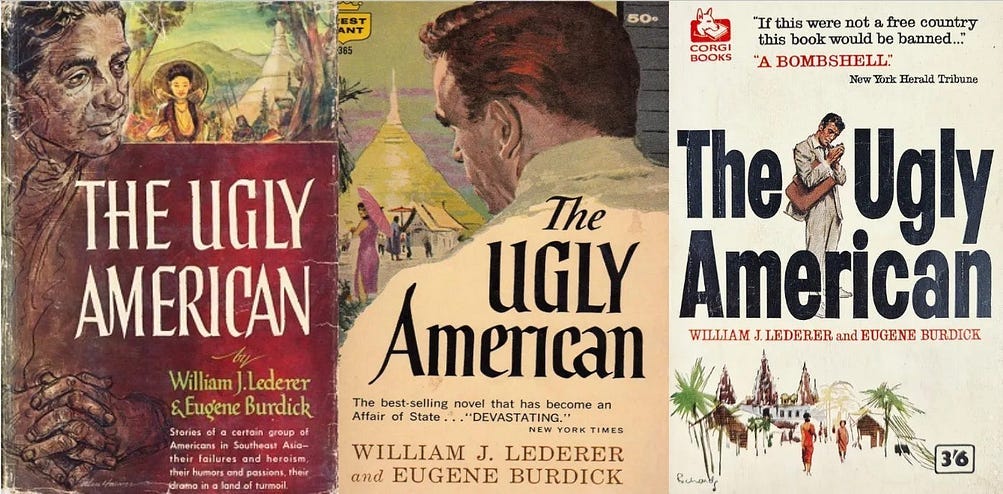

Take The Ugly American — a blunt, semi-fictional expose of U.S. diplomatic failure in Southeast Asia, published in 1958. It wasn’t peer-reviewed. It wasn’t “methodologically transparent.” It was anecdotal, polemical, and built on composite characters. And it had more impact on U.S. foreign policy than a decade of academic papers. President Kennedy reportedly sent it to every member of the Senate. It helped birth the Peace Corps. It told a story about failure — Americans abroad who didn’t speak the language, didn’t leave the compound, didn’t bother to understand the people they claimed to help. That story worked. It hit harder than any academic paper ever could.

Similarly, screenwriter Bruce Robinson’s The Killing Fields, the 1984 film depicting the Khmer Rouge genocide in Cambodia, had an outsized impact on Western perceptions of humanitarian crises and the moral failures of foreign policy. Centered on the friendship between American journalist Sydney Schanberg and Cambodian interpreter Dith Pran, the film personalized the horror of mass killings in a way that academic studies and policy briefings never could.

By focusing on one man’s survival amid ideological madness, The Killing Fields translated abstract numbers — millions dead — into something emotionally inescapable. It played a crucial role in embedding the idea that Western indifference to distant atrocities is not just a policy failure, but a human one. For many, it was the first cinematic reckoning with the consequences of Cold War realpolitik in Southeast Asia — and a reminder that atrocity is most effectively condemned not through theory, but through story.

Meanwhile, scholars with more precise, less dramatic takes languish behind academic corporate paywalls. Users not at universities or thinktanks with a subscription have to pay anything from $15 to $65 to read a single paper! Who’s gonna read that?

And what of the IR academy? It keeps churning. Top journals publish articles that are statistically flawless and rhetorically inert. Theorists debate each other in language no policymaker would touch with a barge pole. There’s a kind of quiet arrogance in all this — an assumption that good ideas will somehow rise to the surface on their own. They won’t. Not in a world where narrative dominates and funding shapes perception.

Think tanks understand this. They’re the real masters of the story game. Their reports are short, sharp, and media-ready. They give officials what they crave: clarity, confirmation, and quotes. But let’s not romanticize them. Think tanks tell better stories because they’re paid to.

And the people doing the paying? Corporate donors, ideological billionaires, foreign governments — they aren’t funding nuance. They’re buying influence. What you get, as a result, is narrative dressed up as analysis. “China is rising and must be contained.” “The U.S. must lead, or chaos will follow.” These are not conclusions — they’re premises, recycled endlessly, to justify the next intervention, the next arms deal, the next round of “strategic engagement.”

It works because it’s simple. Because it’s emotionally satisfying. And because the competition — from academia, at least — is barely trying.

So the question becomes: could the academic world fight back? Could international relations scholars tell better stories — ones that are still rigorous, but also readable, pointed, and powerful? Could they shape the narrative space instead of watching it be overrun by ideologues with slick PowerPoints and a war to sell?

There’s a reason to try. Right now, the policy debate is dominated by voices that aren’t just wrong — they’re bought. They produce certainty where there should be doubt. Urgency where there should be restraint. Academics could disrupt this, if they wanted to. But that would require confronting the perverse incentives of their own profession.

Solving the problem would mean writing with the public in mind. It would mean risking relevance at the expense of tenure. And for many, that’s simply not a trade worth making.

So we’re left with this: a discipline that knows the world is complex, but can’t find a way to explain it simply. A policy world that craves simplicity, and gets it — from people who are more interested in influence than accuracy. And a gap between them that keeps widening, one unread article at a time.

In international relations, the most influential book of the Cold War wasn’t a theoretical breakthrough. It was a pulp novel with a moral message. That’s not just a footnote. It’s the punchline. And unless scholars start telling stories that matter, they shouldn’t be surprised when no one’s listening.