A worst-case scenario for President Lee’s visit to the White House?

In diplomacy, where misinterpretations and symbolic slights can reshape outcomes, ignoring worst-case possibilities isn’t caution—it’s negligence.

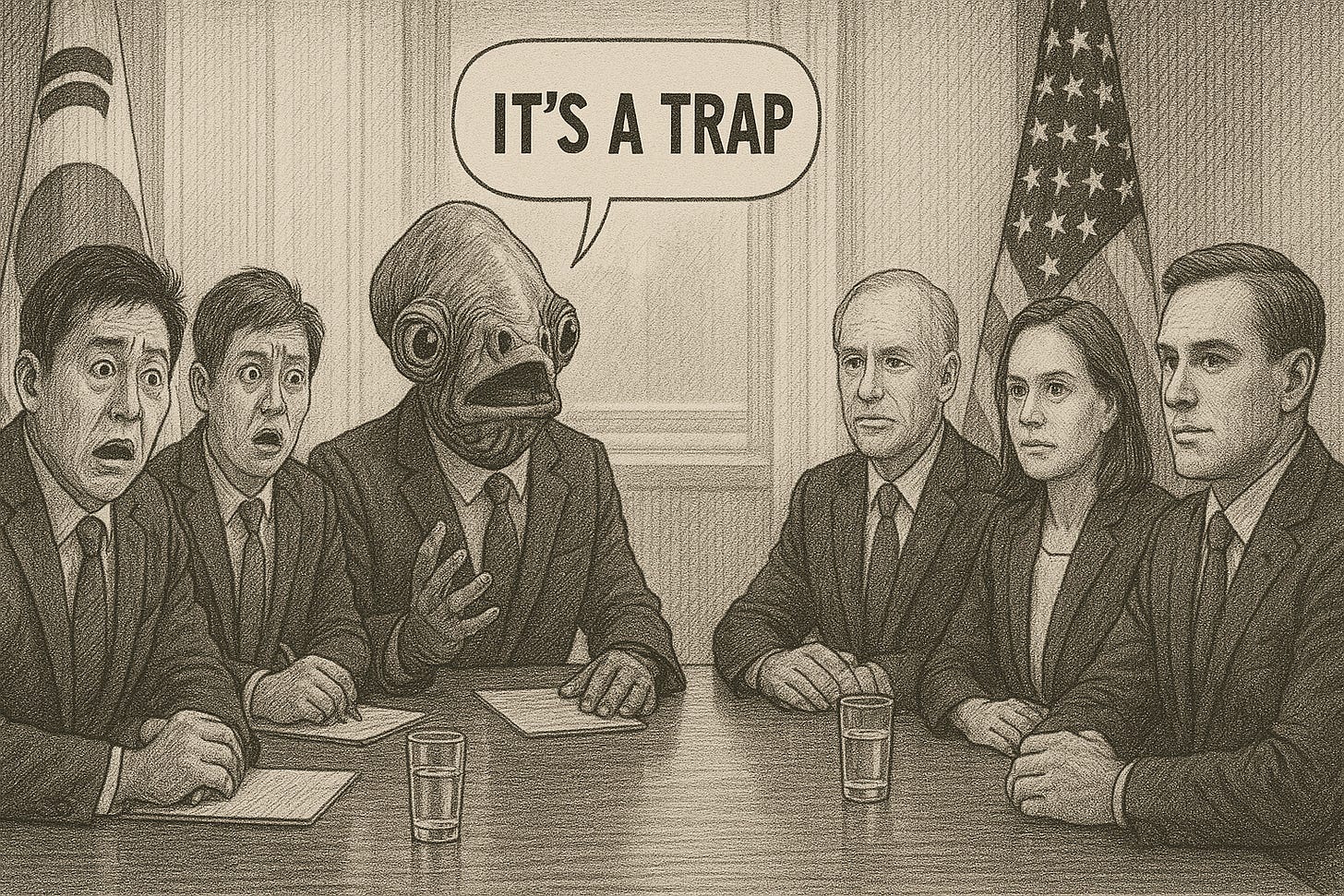

When President Lee visits the White House later this month, it will not be a meeting. To quote Admiral Ackbar—it’s a trap! Seoul shouldn’t just be worried about the immediate outcome but also whether this will be the beginning of the end for the alliance.

Dwelling on worst-case scenarios is not an exercise in pessimism. It’s a necessary practice. By mapping out the most damaging outcomes, we can identify structural vulnerabilities, challenge assumptions of stability, and prepare ourselves for the full spectrum of possible futures. Worst-case thinking forces a confrontation with the limits of control, the unpredictability of actors, and the cascading effects that a single misstep can produce.

In diplomacy, where misinterpretations and symbolic slights can reshape outcomes, ignoring worst-case possibilities isn’t caution—it’s negligence. There’s good reason to worry.

Lee will be tested and humiliated all for a few minutes clout on Fox News. Just watch them—these Oval Office performances are not diplomacy! They are the King and Duke’s “Royal Nonesuch” from The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and we’re the rural townsfolk watching them prance about—only we don’t get to tar and feather them after the show. Am I being too pessimistic?

A series of high-profile visits to Washington have gone painfully wrong.

King Abdullah of Jordan, despite decades of close ties, was left waiting hours before a brief and chilly handshake, and later blindsided by a White House statement undermining his position on Jerusalem.

South Africa’s President Cyril Ramaphosa was visibly sidelined during his joint appearance, with the Trump team using the press conference to rant about tariffs and crime in Johannesburg.

Ukraine’s President Volodymyr Zelensky—desperately needing security assurances—was forced to navigate a Trump monologue about NATO freeloaders and Hunter Biden, with barely a word of substance exchanged.

These are not aberrations. They are the new normal.

What unites these cases is not just disrespect, but a pattern of deliberate marginalisation: staging the ally as weak, needy, and easily manipulated. And there’s every chance South Korea is next.

Despite being one of America’s closest partners—militarily, economically, and strategically—President Lee will find himself cast in the same theatre. There are three reasons why.

First, Trump LOVES to punch down. Like his TACO caricature, and his need for self-representation as tough and muscular rather than flabby and soft, he needs to act tough when he can. He can’t act tough next to Putin, Xi, or Kim, and tolerates dealing with the U.K. and Japan; but South Korea… it will not be so lucky. Ukraine, South Africa, and Jordan are in one way or another, highly dependent on the U.S. Like a slum landlord to a struggling tenant, this gives Trump the opportunity to show how tough he is. South Korea is highly dependent on the U.S. in both economic and security terms. This gives Trump the opportunity to play the slum landlord.

Second, the information on South Korea that reaches even intelligent leaders in the U.S. is limited. What Trump hears and sees will be extremely limited. Trump’s talk to date has shown him to be sorely misinformed (there are 45,000 U.S. troops in Korea), and disrespectful (Korea is an ATM). Worst of all, it also shows that South Korea is actually stuck in his craw as somehow duplicitously associated to Biden (“I got them to pay billions of dollars, and Biden then canceled it”). And all that bile is going to spew right out like a Big Mac at the end of a night on the town.

Third, there’s also a very real chance that racism plays somewhat of a never-mentioned role in Trump’s behavior towards South Korea. Racism underpins aspects of Trump’s foreign policy rhetoric, and his attitude toward South Korea is no exception. His portrayal of South Korea as perpetually dependent on American protection—despite the country's advanced economy and military—echoes a paternalistic worldview rooted in racial hierarchies. By demanding disproportionate payments for U.S. troop presence and labeling Korean trade practices as inherently unfair, Trump implies that Asian allies exploit American generosity, a narrative that mirrors broader racist tropes of the “scheming foreigner.”

So how will Lee handle Trump? Lee is a highly skilful politician and will use interpretation to create space and ambiguity. Zelensky made the error of speaking English. A diplomatic faux pas. With someone like Trump, even when you speak the target language fluently, you always use an interpreter to slow down the conversation.

Should President Lee speak earnestly about shared interests or try to correct Trump’s errors, there’s every chance he’ll be interrupted, sidelined, or reduced to a supporting actor in Trump’s political performance.

The White House under Trump doesn’t function like a traditional foreign policy apparatus. It operates more like the Back to the Future with Trump as Biff, and his cabinet filling the looney misfit gang (Didn’t I read somewhere that the writers based Biff on Trump?)

At face value, the trigger for this meeting is economic. South Korea is protesting the wave of tariffs that have blindsided its key industries—steel, electric vehicles, semiconductors—all sectors it has spent years restructuring to align with U.S. demands. Seoul has bent over backwards to meet Washington’s climate-linked subsidy standards, reshuffled supply chains to reduce dependence on China, and even encouraged national firms to invest heavily in U.S. states favored by the Trump administration.

But none of that seems to matter. Trump talks across traditional diplomatic boundaries. Economics is the same as security, and a trade deficit alters an alliance. Trump has already cast Korea as an “unfair competitor” and is framing the tariffs as a patriotic move. This means the alliance is also at risk.

South Korea’s national strategy is built on twin pillars: export-led economic growth and the U.S. security umbrella. The worst-case scenario for President Lee’s visit is that both erode simultaneously. On the economic front, if Trump publicly accuses Korea of cheating, threatens secondary tariffs, or insists on direct payments in exchange for future exemptions, Korean businesses will begin to reassess the reliability of U.S. market access.

On the security front, if Trump repeats past threats to withdraw troops or demands a fourfold increase in host-nation support payments, Seoul will have to question whether the alliance is still a mutual pact—or just another transaction.

This is especially dangerous because Lee is not visiting as a supplicant. He is visiting as the democratically elected leader that has, for over seven decades, acted in alignment with U.S. regional strategy. But Trump, as 2025 has repeatedly demonstrated, has little interest in shared history or norms. He seeks only performance—and President Lee, no matter how carefully prepared, cannot control the stage.

The worst-case secanario unfolds at a joint press appearance where Trump dominates the microphone, mocks Korea’s trade surplus, and offers no clarity on military support. A few offhanded comments suggesting Seoul “should take care of its own problems with the North.” And then a quick series of events:

Trump lies. He lies boldly about South Korea.

Trump adds an offhand comment, like “If it wasn’t for us, you’d be speaking Japanese right now”.

Lee responds forcefully, and corrects him.

Trump’s fragile ego is hurt and hurt bad.

Then everything becomes personal. Trump says America is “tired of paying for rich allies” and goes on to make up policy off-th-cuff, “We need to withdraw our troops, and we have the mandate and the team to do it.”

The imagery is powerful: Lee standing stiffly beside a grinning Trump, reduced from peer to prop. Then one last statement from Trump.

“We’ll see. Nobody knows what I’ll do, but we’ll see in two weeks.”

In Seoul, the domestic reaction would be swift. Support for the alliance would drop across the political spectrum, from progressive doves to conservative realists. In Tokyo, in Canberra, in Taipei—eyes would widen as yet another U.S. ally is publicly belittled.

It’s no wonder that Australia’s Prime Minister Albanese is taking his sweet time to arrange a visit. It seems that things can only go bad?

In retrospect, the late July meet could be seen not just as a bad meeting, but as a structural turning point. The point at which the South Korean public and elite began to regard the alliance not as a cornerstone, but as a constraint. The point at which diplomatic hedging becomes strategic necessity.

The point at which trust was publicly broken—not by some crisis on the Peninsula, but by a press conference in Washington.

There is still a chance to avoid this. But to do so would require the Trump administration to act like a conventional partner. And in 2025, that’s the least likely scenario of all.